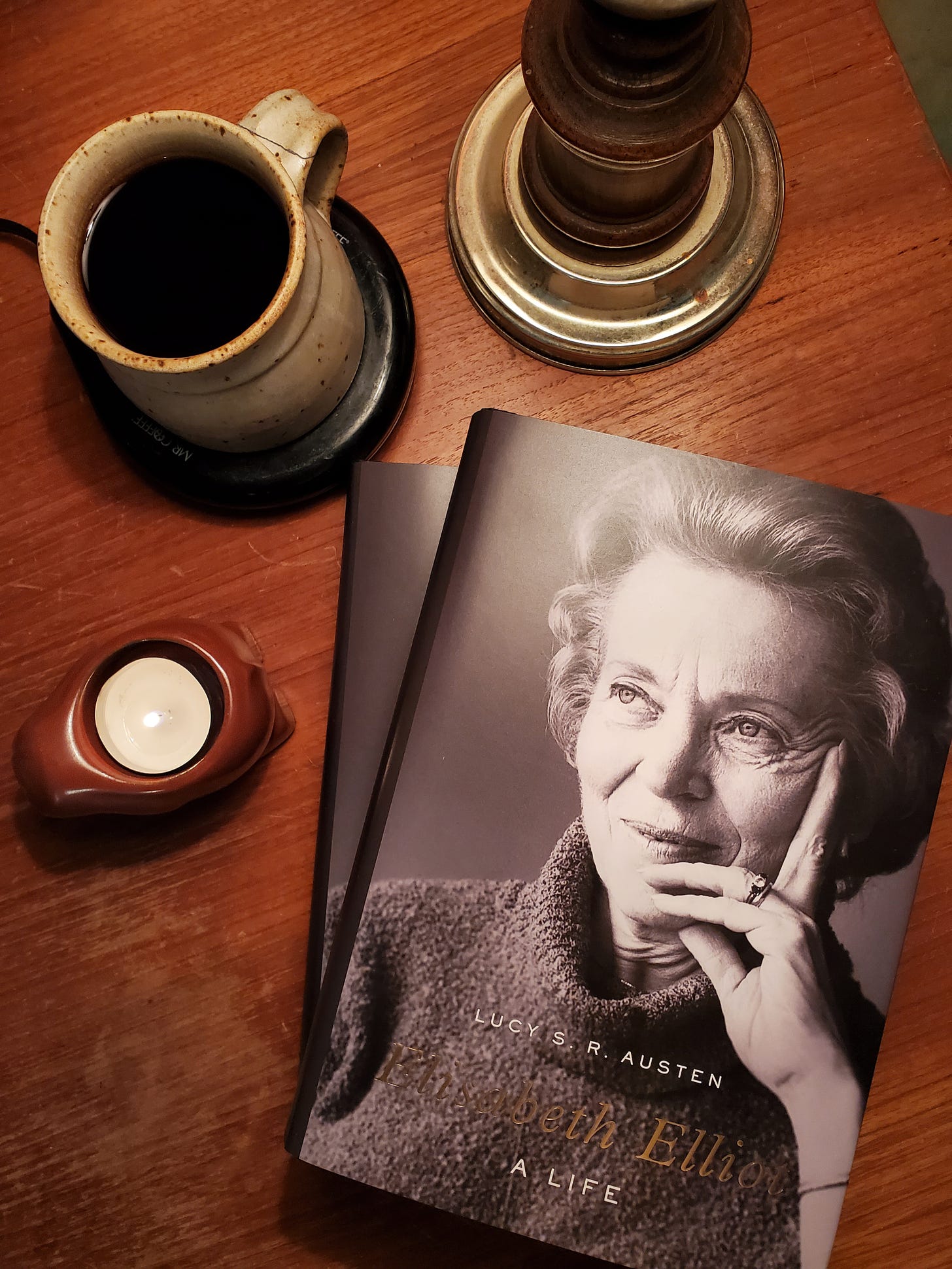

Over the next several months I’m hosting conversations about my most recent project, Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, which is the first full-length single-volume biography of that remarkable and complex woman. We started at the end of September with a one-time conversation covering the whole book, since not everyone has time for an ongoing conversation. Now, for those who have time and interest for more detail, I’m posting once a month for six months—sharing a reading schedule, information about the current section, and questions to start a conversation. This is Part One.

Welcome

It’s a wet, cold day, and the leaves of the witch hazel are crimsoning and dropping outside my window. There’s a good fire in the woodstove not far from where I sit and a ginger cat is curled peacefully on a cushion next to me. It’s a good time to start Part One of the next conversation about Elisabeth Elliot: A Life. Thanks for reading. I’m glad you’re here.

If you’re just joining the discussion, last month’s overview of the book covers some history of how the book came to be, its structure, and some primary themes that emerge from the story of Elliot’s life.

The Schedule

For the month of November, we’ll read and discuss:

The Preface

The Prologue

Chapter 1

Below I’ll share a few thoughts on this section. If you’ve already read this portion of the book or if you don’t mind possible spoilers, dive right in! If you want to stick a virtual bookmark here and go read this section of the book and come back, that’s great too. Either way I hope you’ll join the conversation in the comments section. At the end of November I’ll send the post for Part Two.

The Section

The Preface

I am a reader who often skips prefatory material in my recreational reading. I just want to get to the story and meet it without preconceptions. So if you want to skip the preface, or read the story first and come back to it later, I understand! But first let me make a case for reading the preface this time. This one is pretty short—just over three pages—and it gives some information about decisions I had to make about how to share this story that may be helpful, particularly if you’ve read other books on or by Elliot. It also explains a bit about where this story comes from, because how we know what we know has a lot to do with what we actually know.

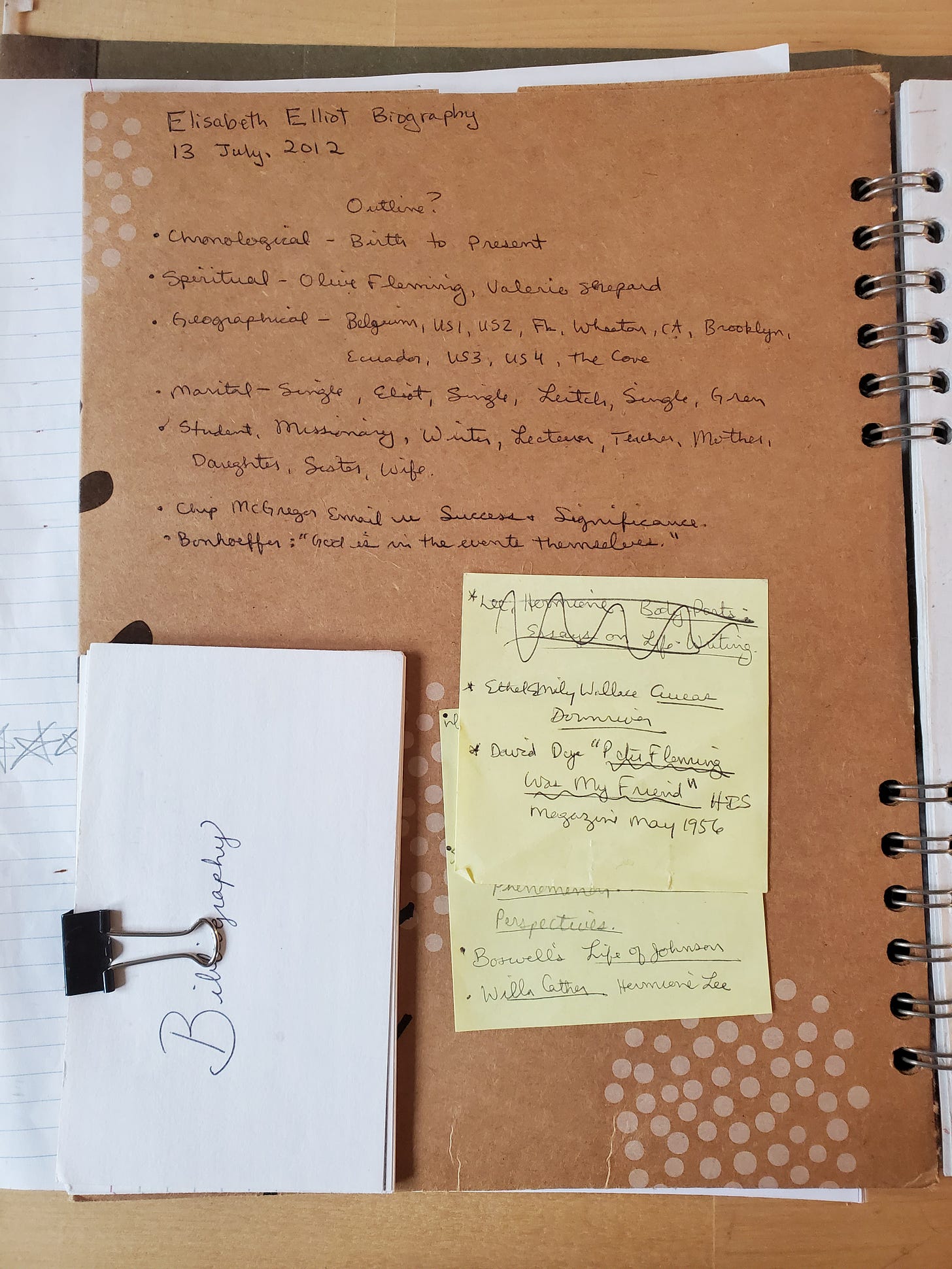

The preface was both one of the first parts and one of the last parts of the book to be written. The information about the names of the Waorani and the final paragraph were, in their first form, footnotes to the prologue and first chapter. But the notes grew beyond the bounds of reason as footnotes and were relegated to endnotes, and I decided that the information needed more prominence than an endnote gives. In its current form, I wrote the preface after finishing chapter 11 and while trying to figure out how to write the epilogue. My writing process is such that once I have a rough draft, however terrible, I can usually start to make some headway, but getting that first draft going can be pretty miserable. So while I was spinning my wheels but still needed to be making progress toward a finished manuscript, I wrote the front and end matter.

The Prologue

Many people are now more familiar with other aspects of Elliot’s work, but she originally became known because of her role in the most widely publicized missionary story of the 20th century. The prologue reintroduces us to that story. It begins at the moment that news of the story first broke, and follows the public story as it was gradually unfolded over days, then weeks, and eventually years to its original 1950s audience.

There is always a tension in retelling this story, for me, because Elliot’s life was much more than this story and one reason I wrote this book is so that we can talk about more than this story. At the same time, without this story it’s likely that we would never have known Elliot’s name. It is part of her life, and its a part of her life that she was asked to talk about for the rest of her life, so it needs to be seen in its proper place.

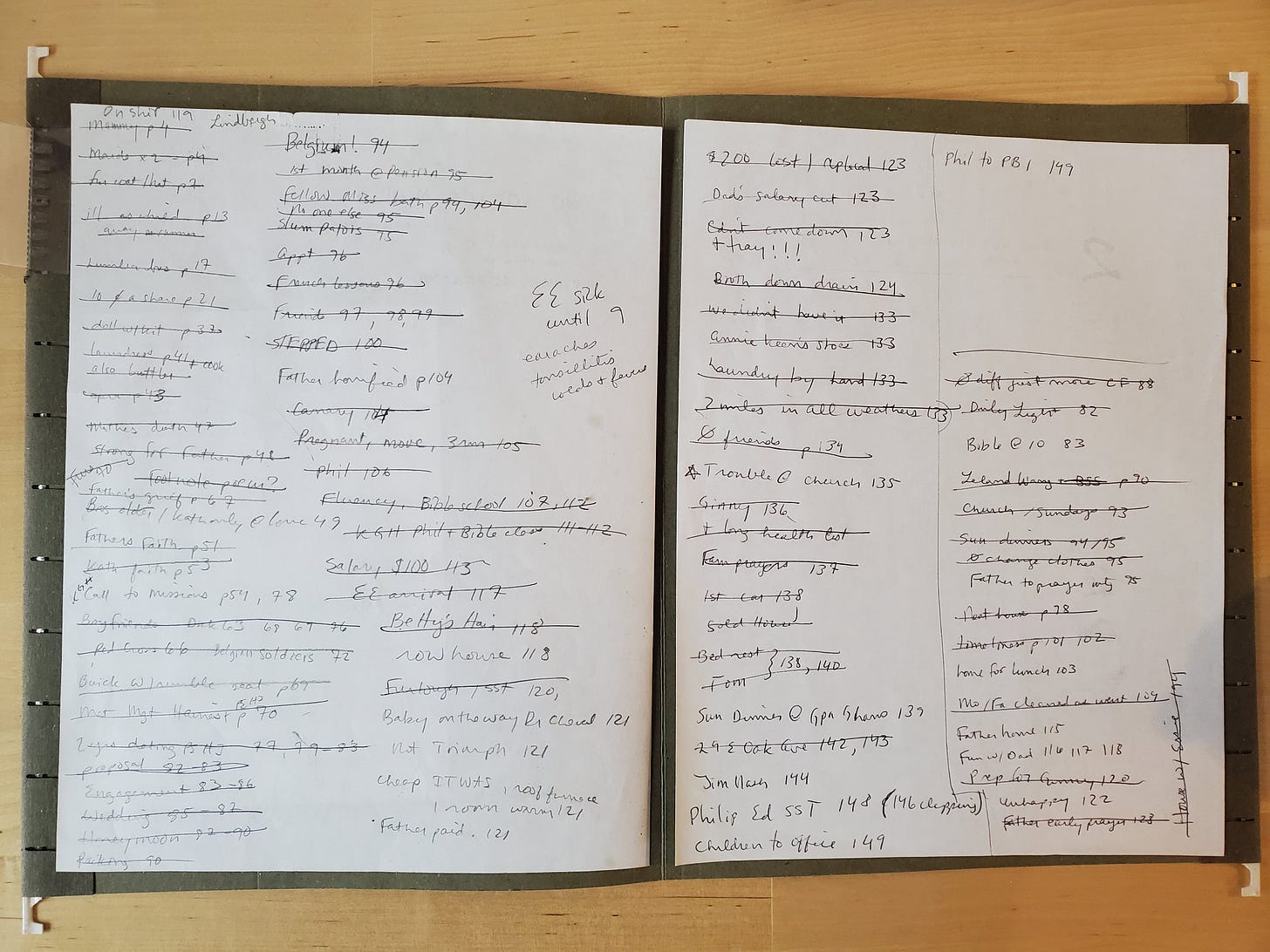

The prologue is the very first thing I wrote, way back in 2015 with papers spread out all around my laptop on a wobbly card table. Throughout the writing process it was important to me, as much as was possible without disrupting the telling of the story, for the book to know only the information that was available at the time, in order to avoid anachronism and to keep in mind what Elliot’s experiences would have been without the benefit of hindsight. The prologue is a first exercise in this. It was fascinating to see the way the newspapers framed the story, and then later on it was fascinating to compare that initial framing with both Jane Dolinger’s travel writing and Elliot’s framing of her experiences with the Waorani. I will have more to say about this when we get into chapters seven and eight.

Chapter One

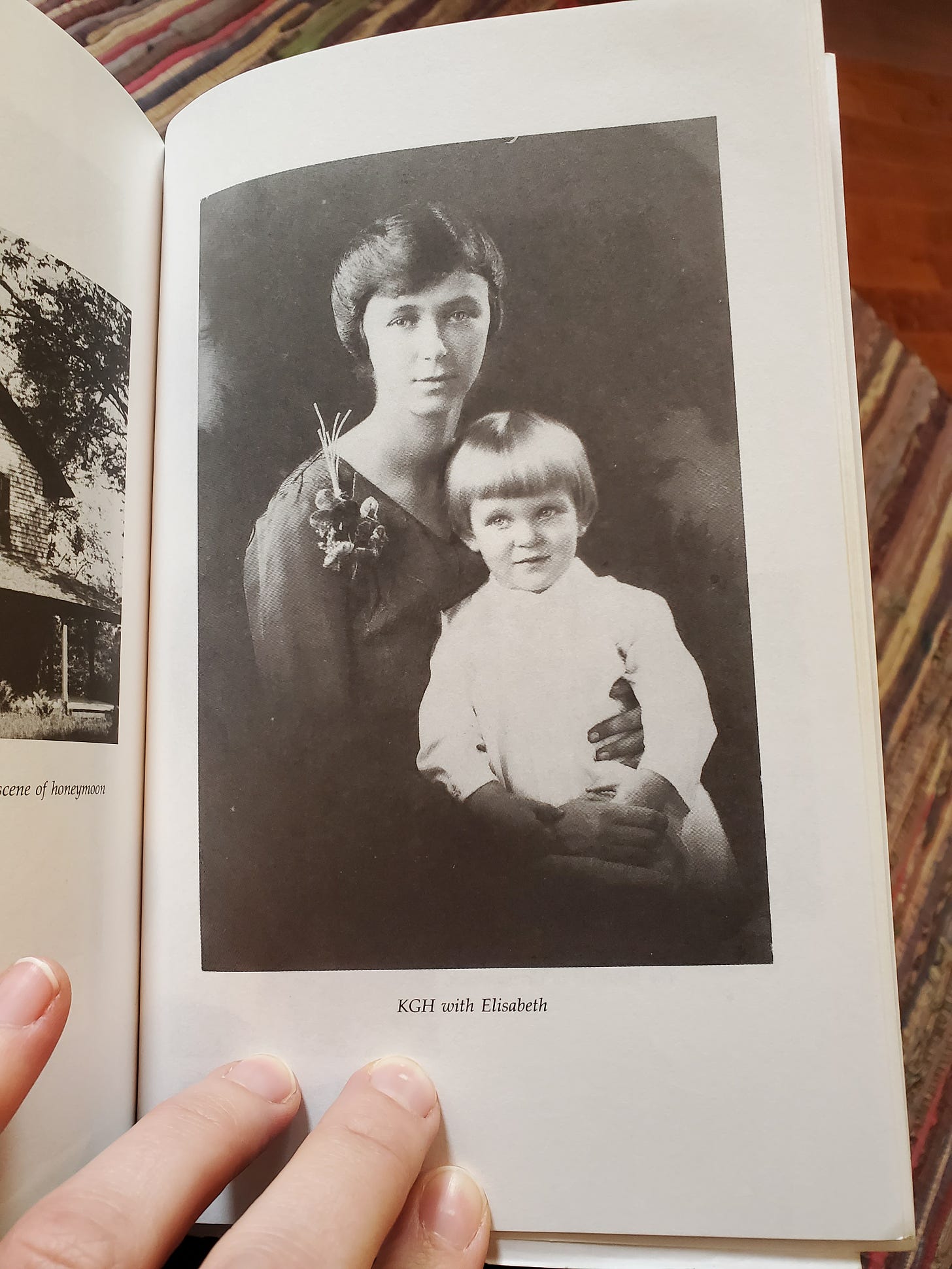

The first chapter provides some brief back-story about the Howard family, and describes the environment in which Elliot grew up. The unpublished memoir of Elliot’s mother, Katharine Gillingham Howard, provided much of the chronology and key events, and gave me one perspective on the feeling of Elliot’s home environment growing up. Elliot’s memories and those of her siblings gave additional perspectives. And Elliot’s wonderful childhood scrapbooks gave a flavor I wouldn’t have otherwise gotten of what she was like as a child and what she did with her days between the more noteworthy events.

I think a good argument can be made that although the wider culture was in the throes of modernism, Elliot’s forming environment was intellectually Victorian in many ways, because of her and her family’s extensive reading of old books. It’s fascinating to ponder how much of her life (or anyone’s life!) flows from inherited traits and the relationship dynamics and cultural mores she lived in growing up, and how much is unique to her irreproducible self. We can pick out things—her mother’s determined cheerfulness, her father’s emphasis on language and writing, her family vacations in the White Mountains, her parents’ ecumenism and their practical demonstration in their own lives of the idea that obeying the will of God could mean doing things you didn’t want to do—that seem to have laid the groundwork for her attitudes, interests, and beliefs later in life. And we can see ways in which she was different from her parents and siblings from the beginning, see her sense of being outside of things and of following her own path.

I began this chapter with Lindbergh’s famous flight for a couple of reasons. Contextualizing her life was a major goal for this project from the beginning. And tying Elliot’s story to concrete historical moments that were occurring at the same time as events in her life really helped me pull her out of the vague mists of history (and perhaps even mythology, with its indefinite “once upon a time”) in my own mind. Every time I got way down in the weeds of her personal papers and felt those mists settling in my mind, I would dig around to figure out what else was going on in the world at the same time. So I wanted to pass those finding aids on to readers.

Also, I’m not a very visual person, in that it’s hard for me to imagine what things look like if I haven’t already seen them. If you’ve seen the numbered apples that have been floating around the Internet recently, you’ll know what I mean when I say I’m a 5/4. The descriptions of what people look like in books usually leave me not much farther ahead than I would have been without them. But Katharine Gillingham Howard’s unpublished memoir includes some photographs, and one of them shows the little family on the steamer, bundled in furs and great-coats. It really brought them to life in my mind. And when I realized that the dates of their trip overlapped with Lindbergh’s, I thought it made a perfect historical anchor-point to start with. Even better, it was an anchor point that included Elliot quite near the beginning of her life, while still giving me a good transition into depicting a little of her family history, which, after all, is the first context any of us has.

Miscellany

This seems as good a place as any to note that while many of the endnotes throughout the book are citations—helpful, but disruptive to the flow of the narrative to check every time one pops up—there are also notes in each chapter that provide key information. Sometimes information ended up as an endnote because including it would have spoiled the flow of a passage, but often the notes are notes instead of text because they broke my “rule” about what the narrative is allowed to know at a given time. This book went through deep cuts to keep it a manageable size, and every note that could possibly be spared was cut, so the ones that are left are important. In fact, I would have split the book between endnotes and footnotes if I could have talked the editor into it, with citations at the back and narrative notes readily accessible at the bottom of the page. So if you tend to ignore endnotes in a book (another habit I can sympathize with!) let me encourage you to pop back at least at the end of each chapter and scan for the notes that add more information

Discussion

There’s a lot more to talk about here, but I’ve already failed in my goal of making this post shorter than the last one so I’ll stop here. I’m looking forward to hearing your responses to this section of the book. Here are some things I’m curious about:

Do you usually read front and end matter? Why or why not?

Did you learn anything new about Elliot’s missionary story from the prologue?

What are your thoughts on the age-old debate on nature, nurture, and individuality?

Where do you see Elliot’s early years forming her, either for good or for bad?

Have you read any of the books that shaped Elliot’s childhood?

What stood out to you in this section of the biography?

Do you have any questions for me about this portion of the book?

My goal for these posts is to get into enough detail to be interesting while keeping the emails to a readable length, so I’d also appreciate feedback about whether that’s working in this post.

Finally, we’re all coming from different backgrounds and experiences and may see things very differently. Feel free to be real, but let’s try to avoid having the comments section become a “don’t read the comments” section. :)

I love endnotes, but stand with you in the opinion that footnotes would have been more convenient.

I have often wondered whether EE would have become a writer--or maybe more specifically a KNOWN writer--without the platform provided by the spearing. I expect that talent trumped platform in her era?

One of the main gifts of your work was the contextualization of EE’s life. I have had the mistaken tendency to think of her as a contemporary figure. Sometimes for better and sometimes for worse, she was shaped by a very specific subset of evangelicalism. Certainly the self-discipline and rigorous biblicism her family instilled were foundational to the person she became.

I am more likely to read prefatory material if it is written by the author him/herself. If it is a modern introduction to an old classic text, I prefer to dive into the text itself and possibly read the introduction later. Forewords, in my experience, are often an excuse to associate a more famous name with the book in the hope of increasing sales. Whether I read them largely depends on if I can finish them in three minutes or less.