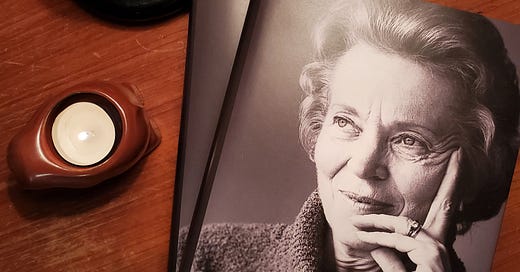

Over the next several months I’m hosting conversations about my most recent project, Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, which is the first full-length single-volume biography of that remarkable and complex woman. We started at the end of September with a one-time conversation covering the whole book, since not everyone has time for an ongoing conversation. Now, for those who have time and interest for more detail, I’m posting once a month for six months—sharing a reading schedule, information about the current section, and questions to start a conversation. This is Part Two.

Welcome

Today is brilliantly sunny and bracingly chilly. We’re using the woodstove daily, burning wood that was cut in our pasture and hauled and split and stacked by all the hands it’s warming now. I’m writing with a mug of hot tea close at hand, and someone is in the kitchen making cinnamon toast, so the house smells wonderful. It’s a good time to start Part Two of the conversation about Elisabeth Elliot: A Life. Thanks for reading. I’m glad you’re here.

If you’re just joining the discussion, last month we covered the Preface, the Prologue, and Chapter One

The Schedule

For the month of December, we’ll read and discuss:

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Below I’ll share a few thoughts on this section. If you’ve already read this portion of the book or if you don’t mind possible spoilers, dive right in! If you want to stick a virtual bookmark here and go read this section of the book and come back, that’s great too. Either way I hope you’ll join the conversation in the comments section. At the end of December (or possibly the very beginning of January, depending on how Christmastide goes!) I’ll send the post for Part Three.

The Section

Chapter Two

When I’m writing, I write until I get stuck, then go back and read what I’ve got, editing as I go, until I can reestablish flow. I write and edit in the document I started with as long as I’m adding new words or making changes at the line level, but every time I want to try a substantial change that I’m not sure will work I make a new document. That way, if it doesn’t work I can easily go back to the point where things went wrong and try again.

Near the beginning of the first version of Chapter Two is one of the “helpful” notes that my editing self sometimes leaves: “This beginning is no good. Find a way to perk it up!” When I come back to notes like this I always wish I had been more specific, but I did eventually iron out the opening paragraph you see now. As I thought about the source material from these years, I was struck by the way the changes in the Howard family were mirrored by changes in the country as a whole. The war touched everything, even for those who were comparatively less affected by it.

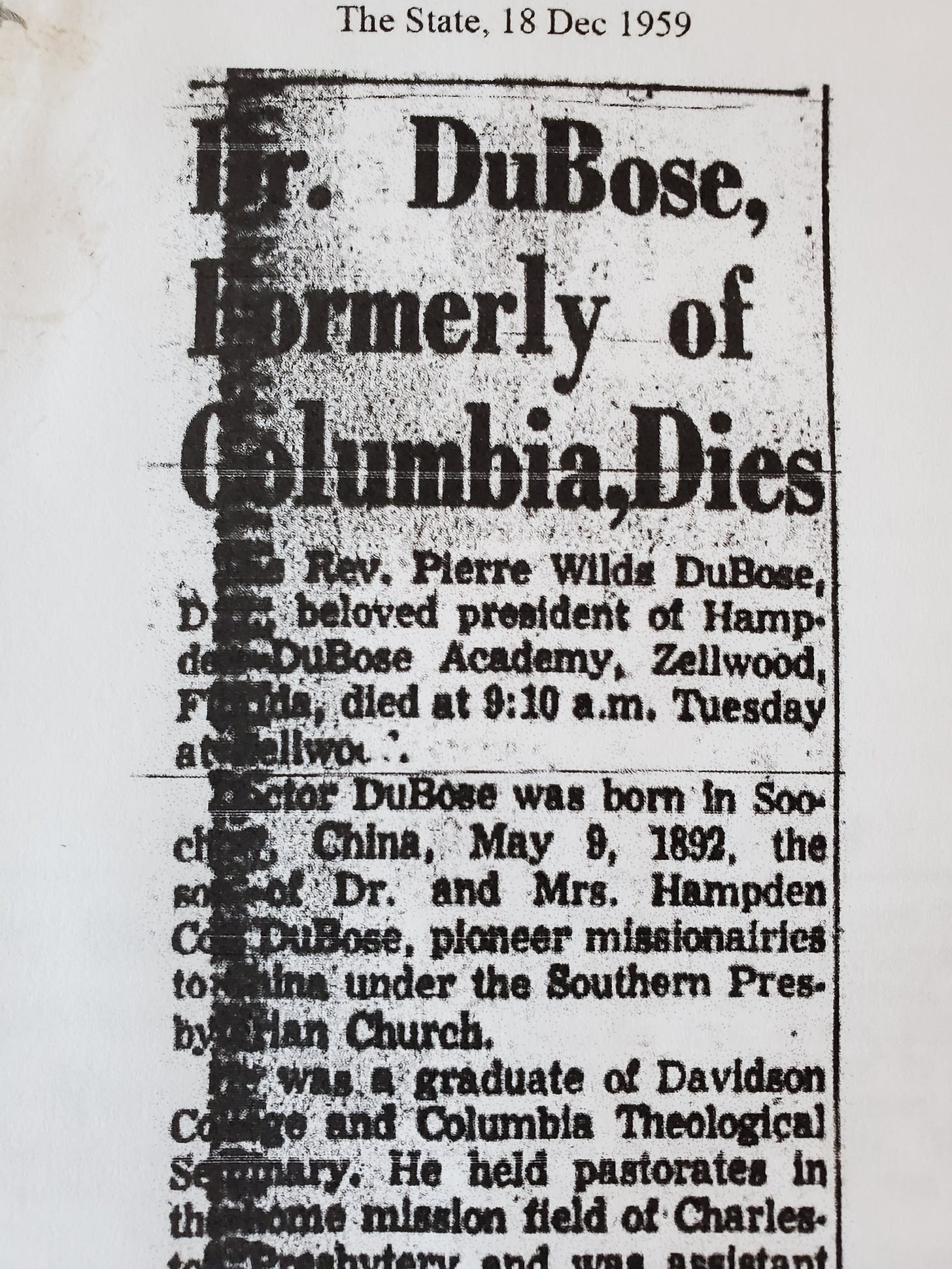

Research for Chapter Two included reading Elliot’s letters and her mother’s unpublished memoirs, refreshing my memory of World War II, learning more about what life was like for the average American teenager in this period, and finding out everything I could about Hampton DuBose Academy. Thanks to the bright side of the Internet, I was able to sit at home and look at old HDA yearbooks, find information about the DuBose family, read memories from other alumni, and even, after prolonged digging, to find Gwynne DuBose’s name. For a long time, the only references I could find called her Mrs. DuBose or Mrs. Pierre Wilds DuBose, and the longer I looked the more determined I became that her given name not disappear. Ultimately I had to request a copy of her marriage license to find it.

In this chapter we get Elliot’s own voice for essentially the first time—not just her voice as an adult looking back at memories, but her voice as it was in her teens, frozen in time. I wish there had been more space in the book to share excerpts from those letters because they’re so evocative. The slang! The drama! The food! I spent a lot of time wondering whether Betty herself was really that interested in the details of what she was eating, or whether she thought that was what her mother wanted to hear about, or whether she was afraid her mother would worry she wasn’t eating enough, or . . . ? She often sounds like an old newspaper society column—and perhaps that’s really the answer to the question of why she was always describing her meals.

One thing that doesn’t really appear in these high school letters are the kinds of logistical discussions about the future that one might expect a teenager to have with their parents—there’s essentially no mention of possible career paths, of going to college, etc. In fact, there’s not much of the conversational back-and-forth that’s evident in letters later on at all; instead her detailed descriptions of social events are punctuated by an almost endless stream of requests for her mother to send her toothpaste and galoshes and stationery and money and so on. Of course the family may have had these kinds of conversations during vacations, but their absence in the letters is particularly striking because Elliot effectively left home at fourteen and these letters were her only connection to her parents for much of the year.

For a long time my working title for this chapter was Change. I finally settled on the HDA motto, Be, Not Seem, for two reasons. First, for all Betty’s immaturity, her desire to be the same person inside and out seemed to characterize her inner life as much as change characterized her outer life. And second, there seemed to be an important tension between, on one hand, that motto and her desire to live up to it, on on the other hand, her adult evaluation of her experiences at the school and of aspects of the Christian culture she grew up in.

Chapter Three

In many ways, Chapter Three lays a cultural foundation for Elliot’s life. It took me fourteen separate drafts to get it into shape—and that’s before it went into the giant document that contained the whole book, which went through further editing both before and after it went to the publisher. It took the most time to research of any chapter, as I tried to understand the history that shaped Elliot’s present. It took the most time to write, as I spent days laying out and rearranging color-coded bits of the chapter all over my family room floor to decide how to organize it. It’s also where some of the deepest cuts were made, as there wasn’t room for most of the background information to actually make it into print. I hope that my knowing the information as the author has informed what remains so that the book benefits from it anyway.

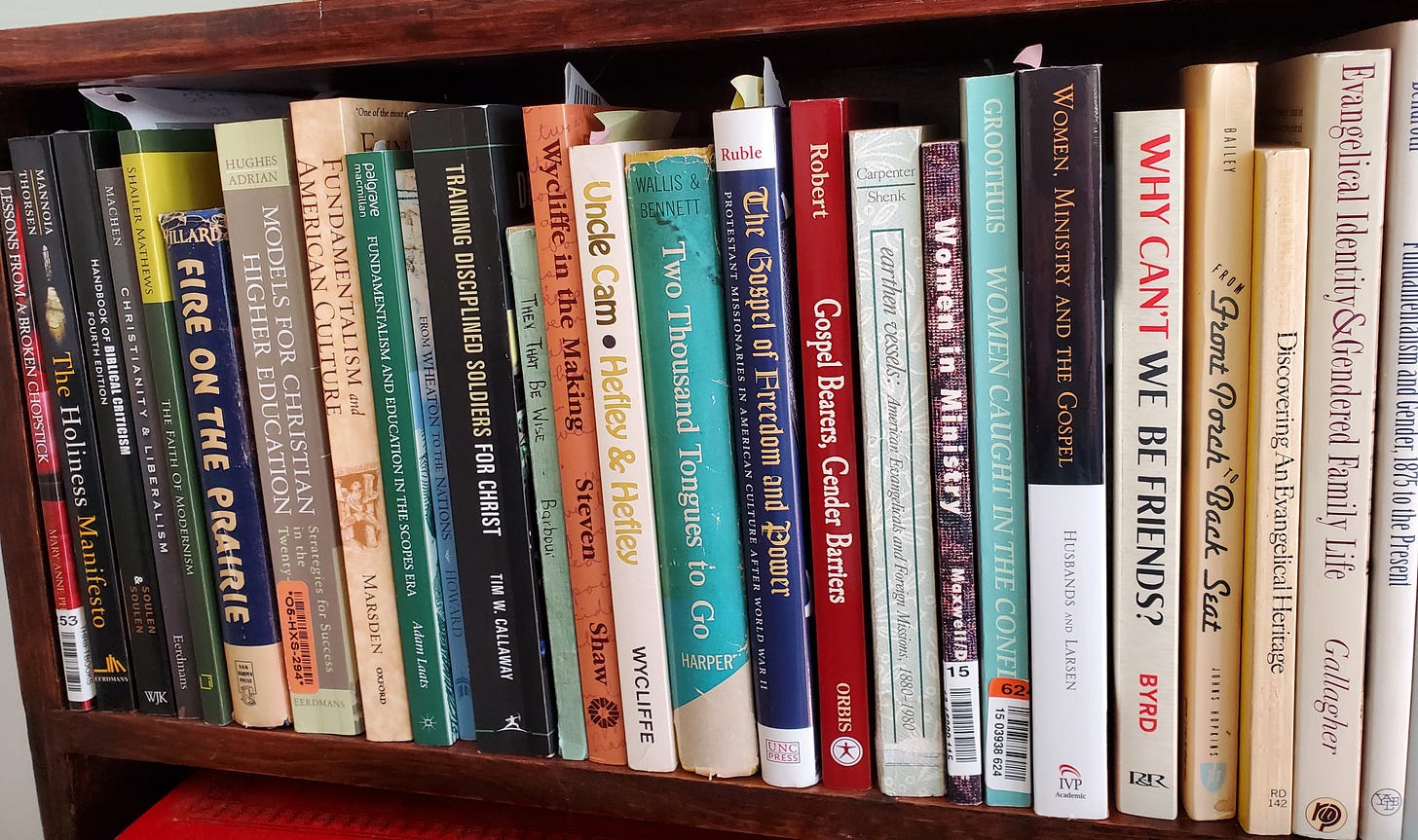

In addition to Elliot’s papers, I read and read and read about evangelicalism, fundamentalism, modernism, missions, the history of Wheaton (the town and the college), the Blanchard family, Christian opposition to oath-bound secret societies, various denominations, various schools of philosophy, segregation, red-lining, the history of racialized language, hazing and the Greek system, selective college admissions, the cost of various colleges in the 1940s, the affect of WWII on college enrollment, the Holiness/Keswick movements, the history of passenger train lines, the evolution of dating in America, and more. All of these things helped to make up the world that helped to shape Elisabeth Elliot, and I’m thankful for the archivists and historians who preserve the information we have about the past and make it accessible.

The history of Wheaton College is, in many ways, a microcosm of the history of American evangelicalism. I found it fascinating to trace the changing trends in philosophy and theology that fed the modernist/fundamentalist debate, to identify aspects of the shift in emphasis from a posture of social-reform “offense” to one of doctrine-centered “defense,” to look at the ways missionary work was viewed during these changes, and so on. Another thing that stood out was the tug-of-war over how to understand and prioritize faith and intellect, or perhaps we could call it the faith of the mind and the faith of the heart. This is epitomized in Chapter Three by the different approaches of J. Oliver Buswell and V. Raymond Edman, and it shows up again and again in subsequent chapters of the book, and continues to be a live issue.

Learning more about all of this history lets us start to recognize some of the ways in which the well-known-missionary-Elisabeth-Elliot didn’t just spring fully formed from the head of Zeus, but came from a specific background, with specific presuppositions and emphases that contributed to how she saw the world and how she made decisions. It’s fascinating to watch Elliot’s voice change over the course of her four years at Wheaton, becoming less 1940s teen slang and more Victorian as her diet of 19th Century reading increases and her focus becomes more consciously “spiritual.” Although by the end of the chapter it’s still very different from the authorial voice she would use in another decade, it has also become night and day different from her voice in letters home from HDA just a few years before.

Discussion

As always, there’s more to talk about than I can fit in this post (they just keep getting longer!), but here are some things I’m curious about:

One challenge in Chapter Two was deciding how to evaluate and integrate the layers of information about HDA. What does one make of the amount of non-academic work required from students? Does it make a difference whether it was to maintain the school or to facilitate the school president’s daughter’s wedding? What does one make of the DuBoses’ decision to provide high school girls as dance partners for GIs at the Victory club meetings? And so on, and so on. What are your thoughts?

Does anything about Elliot’s high school or college experience seem familiar—or totally foreign? (To pick just one example, I had never heard of a “class sneak” before; my high school had a senior skip day but it was much less formal and less communal.)

Elliot did a lot of extra-curricular reading in college, particularly missionary stories and books by Holiness writers (page 49). Have you read or are you planning to read any of these books or authors?

The ability to give and receive “exhortation,” and to evaluate and incorporate (or not!) feedback, is an important part of healthy relationships. But there are many ways that trying to live out that ideal can go wrong. What are your thoughts on how this practice worked out at Wheaton in the 1940s—where it could be emulated and how it could be improved?

Elliot’s book Passion and Purity (subtitled Learning to Bring Your Love Life Under Christ’s Control) is one of the main access points to her work for many readers, and it’s in Chapter Three that the story told in that book begins. If you’re familiar with P&P, how does getting more information here about Elliot’s college-age love life and the history of American dating affect your response to the book?

What are your questions or comments about this section? Do you have any feedback for me?

No need to feel like you have to respond to everything here, but I hope you’ll chime in in the comments about whatever catches your interest. And finally, we’re all coming from different backgrounds and experiences and may see things very differently. Feel free to be real, but let’s try to avoid having the comments section become a “don’t read the comments” section. :)

The research you did on the “specific background” that formed EE was so interesting and important. HDA sounds like a bizarre combination of claustrophobic legalism that was relaxed temporarily whenever the school could benefit from its students’ labor force.

I have thought of EE’s formative process as trying on personalities until she found one that worked. And I think the absence of meaningful content in her correspondence home foreshadows the tension that comes into the story later between her and her mother.

EE’s wide reading and massive vocabulary have been a challenge to me since I started reading her work. I think I have gained a new word with every book 🤣

Oh, BTW, have you read "God the Bestseller" by Stephen Prothero, about the man who was head of the religion department at Harper & Row? It had slipped my mind that that was Elliot's publisher. But it gives lots of background to how the religion department developed and operated.