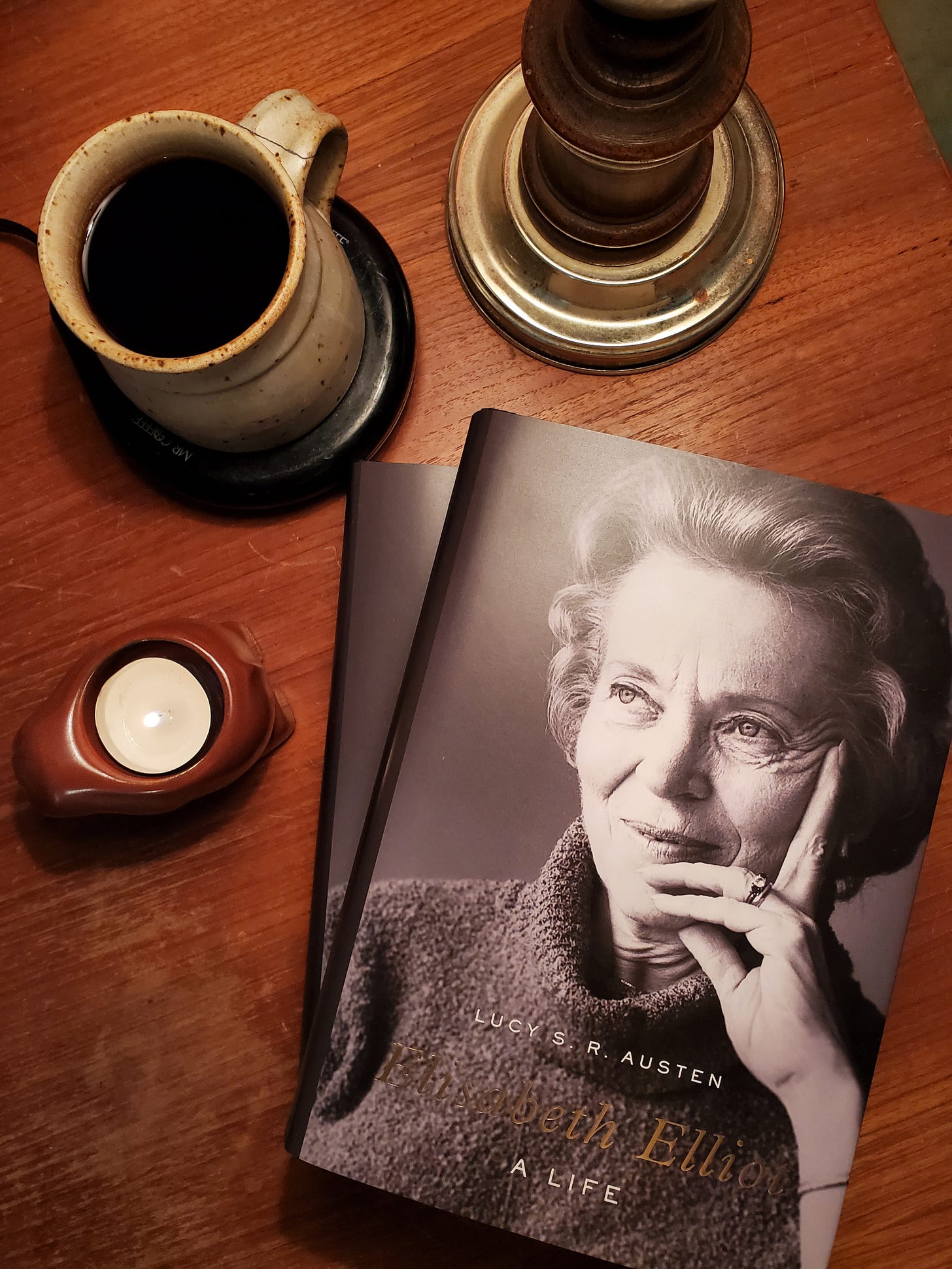

Over the next few months I’m hosting conversations about my most recent project, Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, which is the first full-length single-volume biography of that remarkable and complex woman. We started at the end of September with a one-time conversation covering the whole book, since not everyone has time for an ongoing conversation. Now, for those who have time and interest for more detail, I’m posting once a month for six months—sharing a reading schedule, information about the current section, and questions to start a conversation. This is Part Four.

Welcome

In February of 2020, just before it became apparent that we were in for a global pandemic, this Pacific Northwesterner spent a few happy days in the Billy Graham Center Archives at Wheaton College in Illinois, photographing gajillions1 of newly donated or newly opened documents from Elisabeth Elliot’s papers. One morning it started to snow, and I spent the rest of the day with one eye on my research and one eye out the window, wondering if I was going to have to sleep in the library that night because we were going to be snowed in. No one who worked there seemed concerned, so I kept on with what I was doing, all the while prepared to pack up my things and bolt should they decide to close early. When the usual closing time came and I went gingerly downstairs and out into the cold, I was shocked to find the pavement—steps, side-walks, parking lot, and roads—bare and dry, despite the accumulation on everything else.

That kind of efficient response definitely does not exist in the Pacific Northwest, and it seems like I’ve spent much of January battening down the hatches against a predicted winter storm or hunkered down and waiting for the roads to melt. I’ve inventoried the house and barn and placed orders at the grocery and feed store, cleaned and bedded out stalls, filled water buckets and bath tubs brimful, and cooked a big batch of beans and rice just in case. (Our well has an electric pump, so if the power does go out we lose both our cooking appliances and our water.) I’ve fielded cancellation calls and coordinated rides with four wheel drive both for myself and others. And I’ve come more than once within a hair’s breadth of a cartoon-style slip-and-fall on the ice. However, I am writing this now on a comfortable sofa with two orange tabby cats sleeping peacefully between me and the cheerful fire in the woodstove. Wherever and whenever you are reading this, I hope you, too, are warm and safe. Thanks for reading. I’m glad you’re here.

If you’re just joining the discussion, last month we covered Chapter 4 and Chapter 5.

The Schedule

For the month of February, we’ll read and discuss:

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Below I’ll share a few thoughts on this section. If you’ve already read this portion of the book or if you don’t mind possible spoilers, dive right in! If you want to stick a virtual bookmark here and go read this section of the book and come back, that’s great too. Either way I hope you’ll join the conversation in the comments section. At the end of February (or mayyybe the beginning of March) I’ll send the post for Part Five.

The Section

Chapter Six

One of the first patterns to emerge from the material as I was working on Chapter Six was the constant travel. The Elliots traveled between Brethren mission stations, they traveled to Quito for shopping trips and dental appointments, they traveled to visit various Kichwa villages and settlements, they traveled to missionary conferences, they traveled to Bible conferences for the Kichwa, they traveled singly and together. (And when they weren’t traveling, it seems like they were usually hosting guests!) Because travel was slow and circuitous, a weekend event like a conference would often lead to being away from home for a much longer time.

As I traced routes for various journeys and started calculating just how much time they spent on the road, I was startled by how little they were actually in their own home community. Maybe in my twenties I wouldn’t have noticed, but after a decade of writing this book, after almost twenty years of raising children, it’s the shortness of their time there that stood out. It raised questions for me about how missionary work—and really any work—is and should be done, what kinds of results we’re looking for, how we think about success. It also made Jim’s decision to wash his hands of the Shandians in order to pursue contact with the Waorani seem particularly poignant.

And of course by the time I came in the timeline to the fall of 1955, the impending deaths of the five men overshadowed everything. I’ve written elsewhere about how I think we need to interrogate the way we tell missionary stories, and this story in particular. Writing about it myself reinforced that sense. I had read extensively about the story at various times over the years before setting out to tell it myself, but writing it out was nevertheless unexpectedly affecting emotionally. My writing schedule just happened to fall in such a way that I was writing the events of October 1955 through January 1956 at the same time of year as they had occurred. I was writing with a knot in my stomach, especially during that last Christmas and the week the men were killed. I tried to capture in words something of the effect of the yellowed snapshots, carefully labeled in their album, of little Valerie playing in the river on the afternoon of her father’s death, downstream in the same waters where he died.

Chapter Seven

The first thing to stand out to me on approaching the materials for Chapter Seven was Betty’s frantic busyness in the first year after Jim’s death. In one letter (written, I think, to reassure her mother that she was really doing ok) Betty essentially said that she was so busy during the day that she didn’t have time to feel too sad, and it seems to me that that must have had something to do with the sense of being buoyed up that she had during that first year.2 Running a household and raising a toddler by herself in a rural environment with limited access to labor saving devices was a full time job in itself, and then there was all the administrative and teaching work for the school and church, her language work, her garden, writing a book, international travel—and the amount of correspondence she had to deal with! It certainly didn’t leave her much time for processing what had happened, even had she been inclined that way. The tight rein that she was keeping on herself seemed connected to well-meant but sometimes harsh ways in which she responded to those around her during this time.3

Even after all the heaviness of the week Jim was missing, the news of his death, and Elliot’s first year as a widow, the tone shift in the letters and journals in the second year after Jim died was noticeable. It felt like a gut punch. Her anguish was so great, and her compassion for herself was often so small. Her observation in her journal that it was harder to “find grace to help” (quoting Hebrews 4:16) in the small trials of daily life than in the larger losses she had experienced really highlights the mental shift she seems to have undergone from seeing herself as “newly widowed” to believing that “this is life now.”4 Setting aside for a moment the fact that she was still right in the middle of an enormous loss, I suspect that her experience is not uncommon. Without diminishing the reality of our suffering, it can really help us to bear it if we can fit it into a narrative that gives it meaning and importance. And conversely, when we’re stuck in a long hard slog dealing with day-to-day difficulties in a heavy season of life, it can increase our misery to feel like what we’re suffering from is “small stuff” and shouldn’t be so hard. But during this time we can see the beginning of incremental changes in the way Elliot thinks about suffering and responds to grief.

Discussion

There’s always so much more we could talk about than I can fit in a post, but that might be particularly true this month! Here are some things I’m curious about:

How did living conditions for the missionaries compare with what you had previously imagined? (It was fascinating to me how many things it was cheaper to fly to Ecuador from the US rather than buy in Ecuador—including refrigerators!!)'

What do you make of Betty’s understanding of female submission in marriage seeming to be more restrictive than Jim’s?

I was surprised to find that the rural or pioneering missionaries essentially weren’t meeting with a church for long periods of time, and that apparently no one had a problem with that. Thoughts?

What are your thoughts on Jim’s sense that he’d spent enough time among the Kichwa? Are there principles we can use to decide how long we should stay in a role and how we can define success?

Did you learn anything new about the oft-told story of the deaths of the five men? What are your thoughts on how (and why) we keep telling this story?

Does seeing Through Gates of Splendor set in the context of the build-up, the contact attempt, and the aftermath of grief and loss affect how you view that book? (If I had a magic wand, I would make this biography—or better yet, a book of her published letters and journals—mandatory reading to accompany Gates.)

Were there things about Elliot’s response to grief that struck you as helpful? Harmful?

How does the relationship between Betty Elliot and Rachel Saint strike you at this point? What do you make of Elliot’s persistence in trying to make it work? Does Saint seem reluctant to you, or just hampered by bureaucracy?

What are your questions or comments about this section? Do you have any feedback for me?

As usual, no need to feel like you have to respond to everything (or anything!) here, but I hope you’ll chime in in the comments about whatever catches your interest, even if it doesn’t appear in these questions. And finally, we’re all coming from different backgrounds and experiences and may see things very differently. Feel free to be real, but let’s try to avoid having the comments section become a “don’t read the comments” section. :)

That’s an official count ;)

Page 230, for those of you reading in the print version.

Betty’s letters from this time record, for example, her attempts to encourage Olive Fleming to strive for spiritual victory over her circumstances. Olive would later remember, “I tried to be ‘strong’ because it was somehow expected of me; showing emotion apparently diluted one’s Christian witness before others. But at times grief washed over me in waves, and I could not hold back the tears. On one such occasion, Betty, who had remained stoic through the whole ordeal, chided me: ‘You are just feeling sorry for yourself,’ she said. ‘It isn’t out of love for Pete that you’re crying.’”

Elliot was not the only one of the widows who seemed to feel that cheerfulness in the face of loss was evidence of God’s grace. She would later remember Marj Saint saying to one sympathetic visitor who offered “a shoulder to cry on,” “I really appreciate that, but I trust that the Lord is going to give us all grace so that we won’t even need any shoulders to cry on.”

Olive Fleming Liefeld, Unfolding Destinies: The Ongoing Story of the Auca Mission, 210.

Janet Anderson, “Knowing God’s Keeping Power,” ch.4 of “At Your Service: The Life of Marj Saint Van Der Puy” Series, Confident Living, April 1998, 5.

Page 241 in the print version.

I'm really struck by your comment about having so little compassion for herself. I was struck by it in the book too, but your phrasing here sums it up perfectly. And because of that, she couldn't have compassion for her fellow widows, which seems downright tragic.

Missionary and child of missionaries here. I think missionaries being out of fellowship with a local church is still surprisingly common. And when it was addressed (as it has been in my context), individuals are sometimes shocked/offended at the suggestion that their lack of connection to a church is a potential problem.

I think it IS a problem, as fiercely driven people need community to help wear down some of those sharp edges. The inability to exist in community is not a good sign.