Over the next few months I’m hosting conversations about my most recent project, Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, which is the first full-length single-volume biography of that remarkable and complex woman. We started at the end of September with a one-time conversation covering the whole book, since not everyone has time for an ongoing conversation. Now, for those who have time and interest for more detail, I’m posting once a month for six months—sharing a reading schedule, information about the current section, and questions to start a conversation.

Welcome

A happy sixth day of Christmas to you! I hope you’ve had some sweet times amidst the busyness of the past weeks, and that sitting down to read this post with a mug of something hot to drink will provide a few quiet minutes of rest. Thanks for reading. I’m glad you’re here.

If you’re just joining the discussion, last month we covered Chapter 2 and Chapter 3.

The Schedule

For the month of January, we’ll read and discuss:

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Below I’ll share a few thoughts on this section. If you’ve already read this portion of the book or if you don’t mind possible spoilers, dive right in! If you want to stick a virtual bookmark here and go read this section of the book and come back, that’s great too. Either way I hope you’ll join the conversation in the comments section. At the end of January I’ll send the post for Part Four.

The Section

Chapter Four

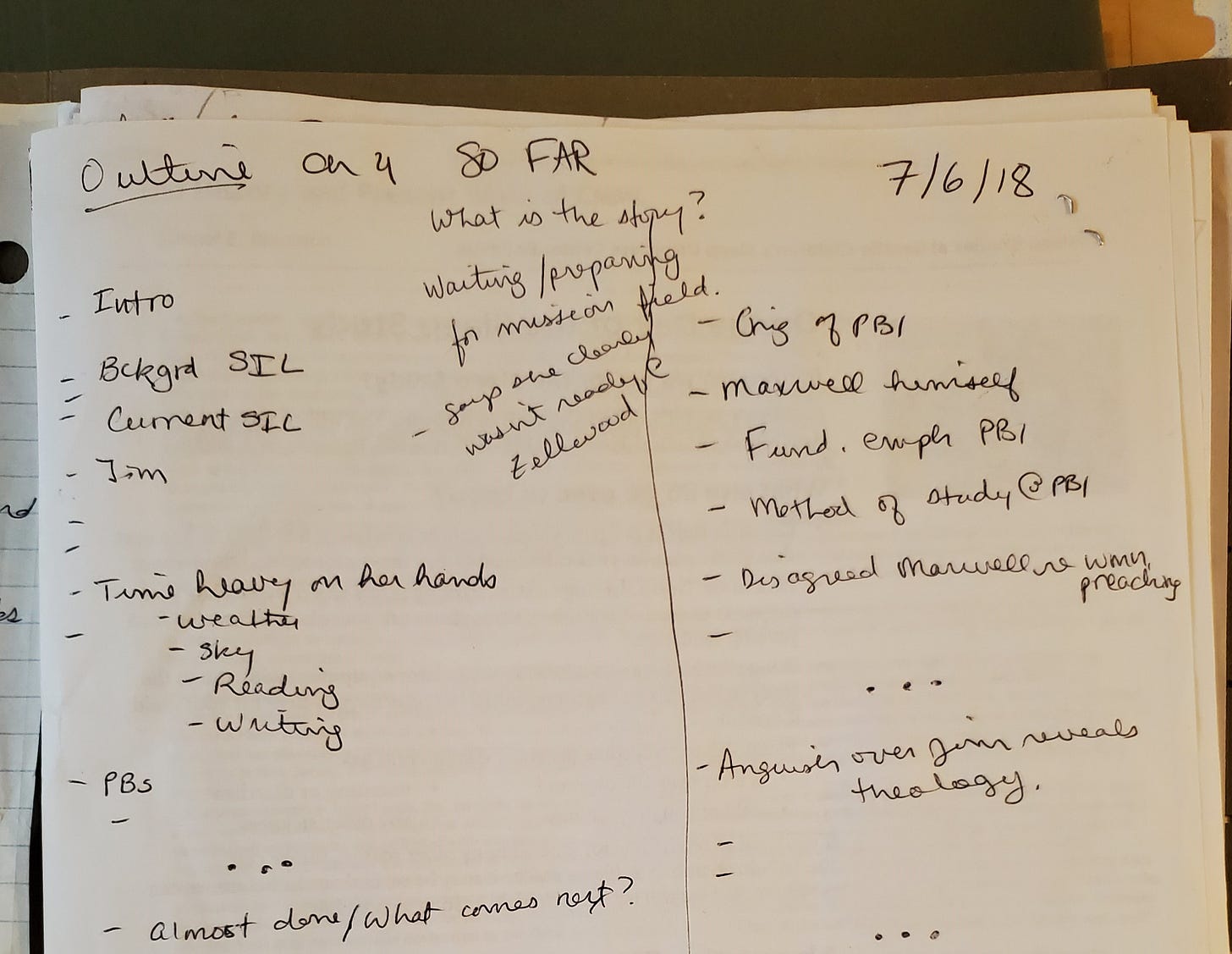

This chapter was exciting to write because it covers several periods of time where the previously-available story of Elliot’s life (in her published work, the author biography on her website, etc.) gave very little or no information. Even with access to Elliot’s correspondence, questions remained at various points about where she was, what she was doing, how she reached decisions, and so on, and it was rewarding to chase down as much of that information as possible.

Filling in the background for Elliot’s life during this time included learning more about the institutions she was involved with. The Summer Institute of Linguistics, where Betty got her training in linguistics and translation, began because Cameron Townsend was a failed Bible salesman: He had dropped out of college to sell Spanish Bibles in Guatemala, only to discover that the people he was trying to reach largely didn’t speak Spanish. With no formal training he embarked on his own translation project, relying on books in the growing field of linguistics to guide him, and this self-taught academic background and practical experience provided the foundation for SIL, which he and a friend started with three students in 1934. SIL benefited from the burst of interest in linguistics during World War II, and by the time Betty enrolled in the program it had grown into a well-staffed program catering not only to prospective missionaries but to foreign language majors and instructors, ethnologists, merchants, pilots, those interested in travel or living abroad—anyone who might benefit from an understanding of how languages work and how to approach an unfamiliar language. This history underscores both the necessarily-introductory nature of Betty’s training—a summer course is just not very long!—and the academic footing on which it was based. (Also, I have to comment again on how funny I find it that she wrote letters during Eugene Nida’s Kichwa lectures because she didn’t think she’d ever need the information!)

The history of Prairie Bible Institute, too, sheds light on the atmosphere in which Betty was living during this time in her life. L. E. Maxwell and J. Fergus Kirk, who founded PBI, were “so sure that Christ would return right then, we didn’t think it worth keeping records. We possessed only three file cabinets. When the third got full, we threw out the contents of the first and started over again.”1 They were far from alone in their belief. In 1950, the elders of Jim Elliot’s Plymouth Brethren church were convinced that they were “within forty years of the millennial reign of Jesus Christ, and that’s a conservative estimate!” Jim’s response was, “How poorly will appear anything but a consuming operative faith in the person of Christ when He comes. How lost, alas, a life lived in any other light!”2 This attitude is also reflected in Betty’s decision, when she sold a poem for three dollars, to donate the money to friends who were struggling to raise funds to get to South America with the Christian Airmen’s Missionary Fellowship, even though her own fees for the year at PBI were not yet paid.3

It’s hard to briefly describe how much research went into some pretty short passages of this book. The little paragraph on page 107 describing where Betty was and what she was doing in the fall of 1949 took awhile to nail down. So did figuring out where she was between her time working at HDA and her stint as a boys’ summer camp counselor, and ironing out the details of her time in Brooklyn. One small but time-consuming section that seems particularly pertinent deals with how Betty finally made the decision to go to Ecuador. The impression given in Through Gates of Splendor is somewhat different from the impression given by the available journals and letters. As with other aspects of Betty and Jim’s relationship, it seemed worth nailing down just what did happen as nearly as possible, since so many people have read about their romance in Passion and Purity.

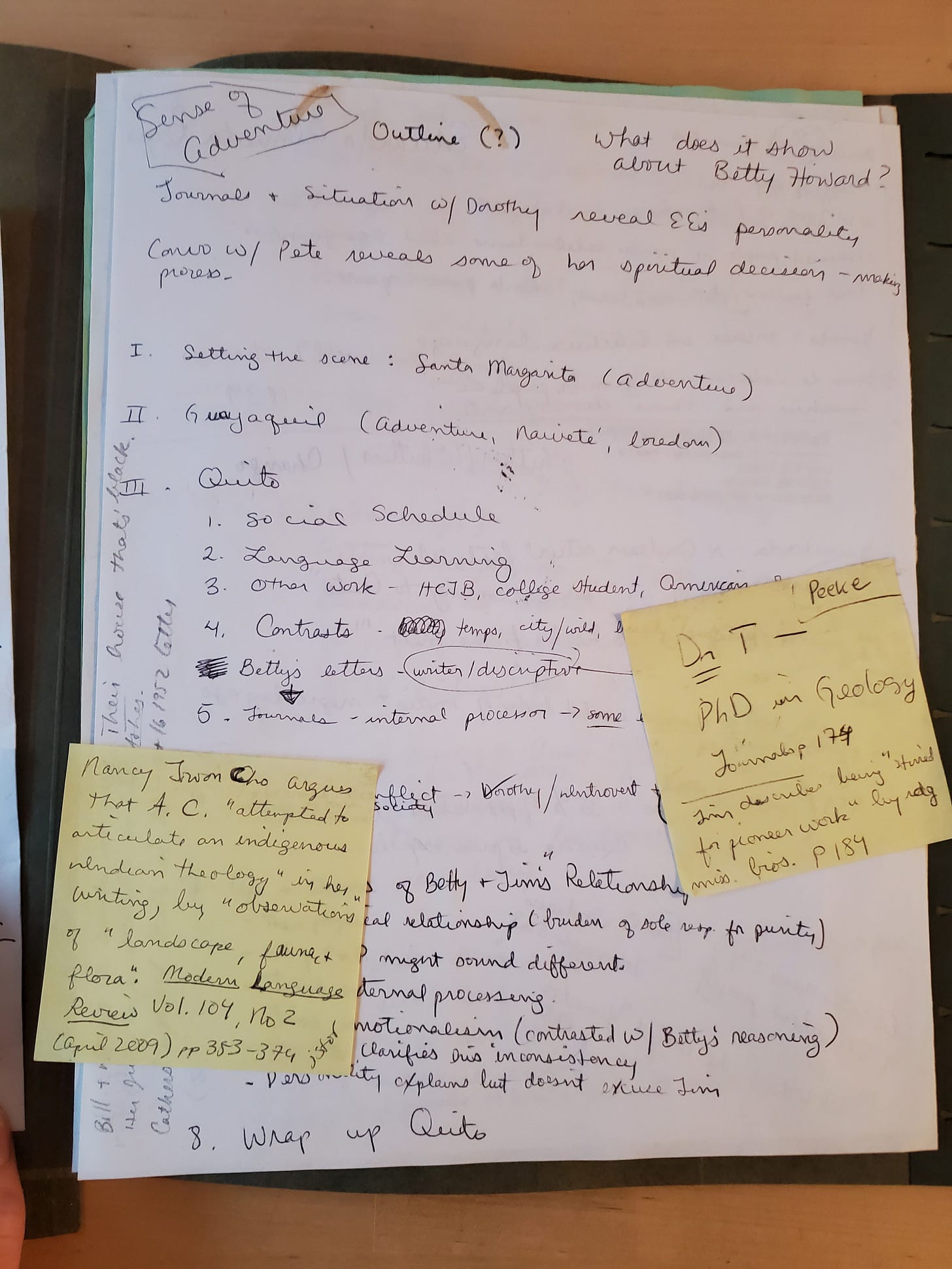

Chapter Five

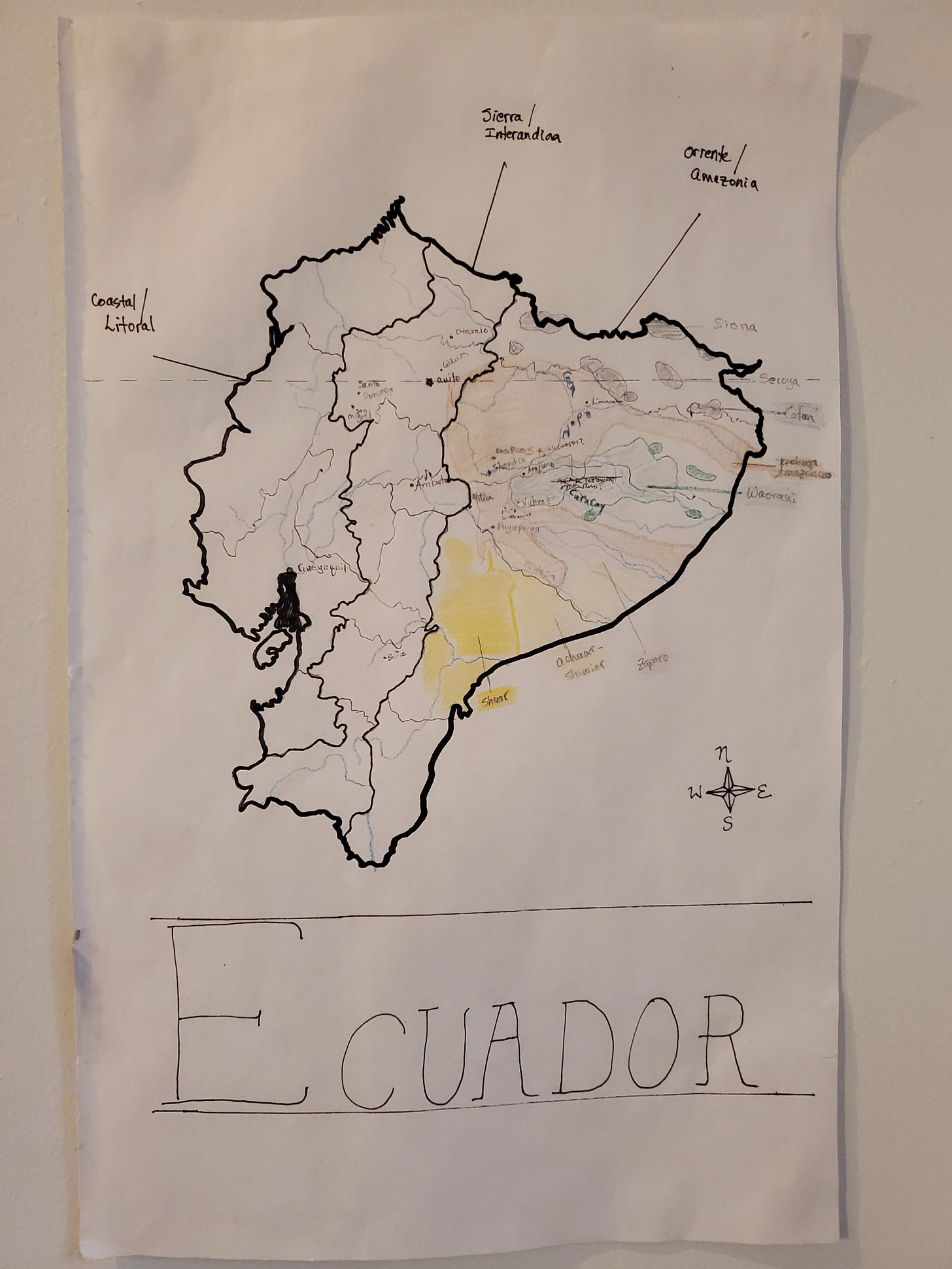

In this chapter, Betty finally arrives in Ecuador, “my home from how on,” as she calls it. Life in rural Alberta had exposed her to difficult things, and Guayaquil and Quito continued to provide culture shocks. Background research for this chapter included the history of shipping lines and airlines, Ecuadorian politics, and Catholic/Protestant violence. Here, too, there were lots of little gaps in the details of Elliot’s experience to fill in. I had no idea before I started research for this chapter how unplanned, unsupervised, and unstructured things were, at least for the Brethren missionaries, with, for example, Betty arriving in the country still with no plan as to where she would be working. I was also startled to learn of the social pace in Quito, which really stands out when you see a list of the dates for social events during the first two months Betty was in Quito: April 29, April 30, May 1, May 3, May 4, May 5, May 6, May 10, May 11, May 13-14, a gap for a week-long missionary conference, May 26, June 6, June 13-14, June 15, June 23. On some of these dates there was more than one event in a day.

Another thing that blew me away was the amount of travel the Brethren missionaries were doing. To take just one small example, when Betty moved from San Miguel to Dos Rios to learn Kichwa, she went first from San Miguel to Santo Domingo, where she spent the night in Dorothy Jones’s storage shed. (She didn’t get much sleep, since there was a group of rowdy drunks outside all night, and the door couldn’t be locked from the inside.) From Santo Domingo she had a long ride north and east to Quito on a banana truck. She stayed in Quito (with the Tidmarshes) for four days, sorting her stored goods and visiting with other missionaries. From Quito she traveled south and west by bus to Ambato. Normally she would have taken a bus from Ambato to Shell Mera, but the road had been washed out over an 8 km stretch, so she planned to fly.

Weather grounded her flight for 24 hours, and she had to spend the night in Ambato (where the bathrooms were, according to other missionaries, the worst-smelling place in the world). She was grateful to receive an invitation to spend the night in the home of an Ecuadorian family. The next day she flew south and east to Shell Mera. From Shell Mera, a Mission Aviation Fellowship plane took her north and east to Tena, the closest landing strip to Dos Rios. From Tena, Betty walked twenty minutes to the Misahuallí River with two Kichwa men who carried her luggage, and for the final leg of her journey she was paddled across the river in a dugout canoe. She had travelled almost three times as far as she would have on long as it would have been on a direct route.

Discussion

As always, there’s much more we could talk about than I can fit in a post of any remotely reasonable length, but here are some things I’m curious about:

What do you think of the underlying theology revealed by Betty’s response to her relationship to Jim in these chapters? Or by her response to the culture at Prairie Bible Institute? Or by her decision to join the Plymouth Brethren? Or by the way she approaches decision making/views waiting for God’s guidance?

What do you make of the the fact that Betty’s position on women teaching in the church was apparently more restrictive than that held by her father? Or of her decisions to teach despite that position?

Was Katharine Howard right to be concerned about Amy Carmichael’s influence on Betty?

What do you make of the course of Betty and Jim’s relationship? Or their lack of clear vision of themselves? Or the parallels between the advice in Passion and Purity and the mainstream-culture dating advice/etiquette books of her youth?

What do you think of the strengths and weaknesses of Betty’s missiology as it appears in Chapter Five?

What are your questions or comments about this section? Do you have any feedback for me?

As usual, no need to feel like you have to respond to everything (or anything!) here, but I hope you’ll chime in in the comments about whatever catches your interest, even if it doesn’t appear in these questions. And finally, we’re all coming from different backgrounds and experiences and may see things very differently. Feel free to be real, but let’s try to avoid having the comments section become a “don’t read the comments” section. :)

L. E. Maxwell to Donald Aaron Goertz, quoted in Tim Callaway, Training Disciplined Soldiers for Christ: The influence of American fundamentalism on Prairie Bible Institute (1922-1980), (WestBow Press, 2013) xxxvi.

Elisabeth Elliot, Shadow of the Almighty (Harper and Brothers, 1958) 115.

Elisabeth Elliot, letter to family, November 10, 1948.

The word that EE’s life shouts from this era is “unmoored.” It comes through in her own voice in These Strange Ashes, so it didn’t surprise me to find it in her bio—except that it clashes so strongly with her public persona as a speaker/author. Her relationship with Jim, her inability to make a decisive move in any meaningful sense seem to be represented visibly in her crazy travels from pillar to post.

The practical theology of PBI and the prevailing conservative Christian culture of her young adulthood was pretty unlivable. Somehow God was expected to preside over the details of life decisions, and the excruciating task of waiting meant that a good number of “decisions” were made by default.

Which leads to the “dating” relationship with Jim… Unmoored, and so very sad.

I agree with everything Michele says in her comment. Yes: unmoored is the word. If this is what moment-by-moment trust in God's leading looks like ... wow. And Lucy I noted the dryness of your statement on page 113: "it appears that the 'several events' [closing EE's door to the South Seas and opening the way to Ecuador] were actually a visit from Jim."

Many aspects of Jim and Betty's relationship bothered me, but the part about him telling Betty how much his family detested her was excruciating. It was almost sadistic. Unbelievably, he referred to it as "betraying my folks before an outsider" -- as if he was more concerned that telling Betty this would make his family look bad in her eyes, rather than that she would be hurt. Their whole relationship was quite painful and sad to read about: the obsession with the specifics of "God's will" and the sense that they were exceptional and had a uniquely high calling that necessitated their painful, perplexing courtship.